Finnish seafarers in the camps on the Isle of Man

The Red Cross archives contain the names of 420 Finns interned on the Isle of Man. Part of them stayed on the island for years, while others spent shorter times there; their number was hardly this high at any one time. Finns were also interned in British colonies.

Manx internment camps

The Isle of Man is a self-governing British Crown Dependency in the Irish Sea, about half way between Great Britain and Ireland. Its population numbered about 53,000 during WW2. During the war, a major part of enemy citizens in Great Britain were interned there, the largest groups were Germans and Italians. Many reasons explain the selection of the Isle of Man as a place of internment. Its remote location made fleeing difficult. The island featured several holiday resorts and inns that were unused due to the war; it was easy to convert these into dwellings for the internees. The Manx had experience in such activities: there had been internment camps during the WW1 already.

There were nine internment camps on the Isle of Man. The Finns were initially placed in Palace Camp in the capital Douglas, but the camp was closed in November 1942. About 80 Finns were then fully released, and most of them signed in the British merchant fleet. The rest were taken to Mooragh Camp in Ramsey. Their neighbours there were Germans and Italians, but the nationalities were separated in their respective departments. The camp buildings were hotels, inns and private homes along Mooragh Promenade.

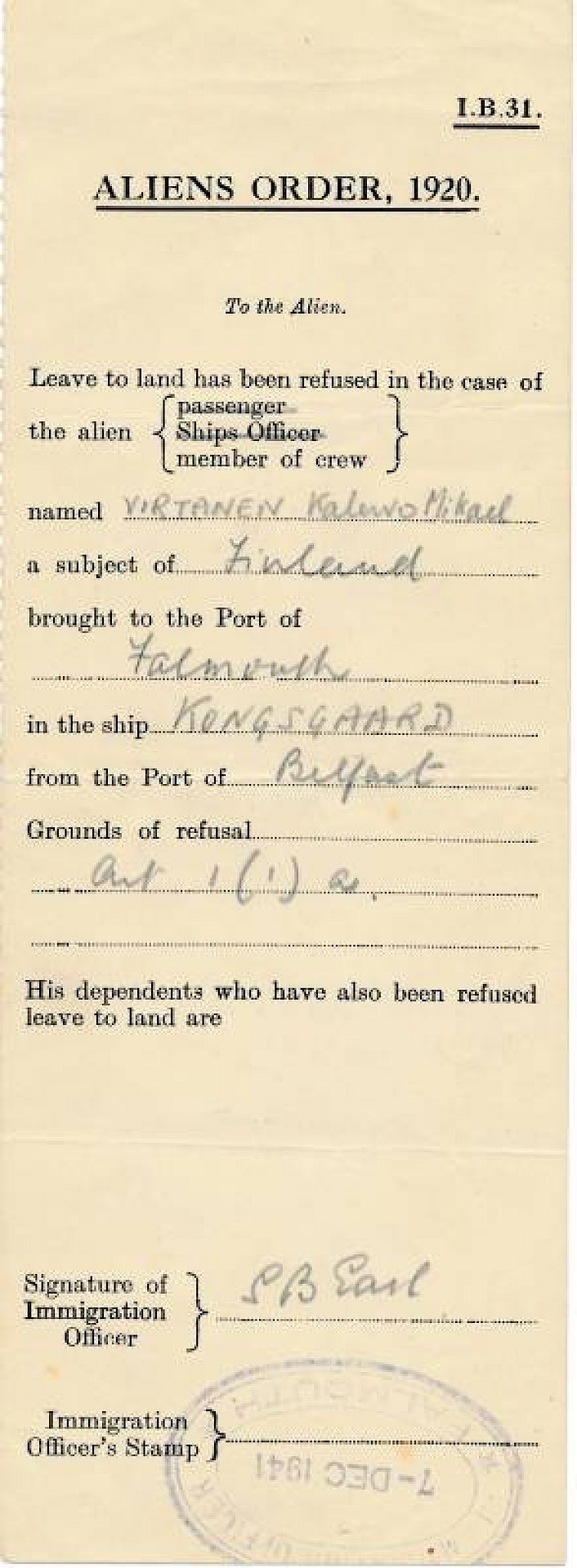

Picture below: Aliens Order, informing Finnish seaman Kalervo Virtanen that he is denied leave to land in Falmouth, England, 7.12.1941. Great Britain had declared war on Finland the previous day. Kimmo Virtanen's collection.

Some were freed - but not unconditionally

The Finnish internees were offered the opportunity to sign on British merchant ships. Qualified seafarers were constantly needed for the perilous voyages across the Atlantic, to carry American war provisions, fuel and food to Britain. Many men took this opportunity, some obviously because they wanted to get out of the camp. There may have been political reasons as well: some Finns hoped that the Allied Powers win the war, so they wanted to help. Emil Ahola and Kalervo Virtanen say that Finns were also persuaded to join the British armed forces, although the United Kingdom and Finland were at war. No certain data exists of any Finnish internees having joined the British armed forces.

Notorious Finnish reputation

The Finns in the Mooragh camp were known as somewhat frightening and violent people. They were divided into two political groups in the camp. The sympathies of one group were with the Allied Powers, and those of the other group with Germany and its allies, including Finland. As those in favour of the Allied Powers left the camp to serve on British ships and to work in Britain, the remaining German-minded became the majority among the Finns on the Isle of Man.

Quarrels arose between the groups, often boosted by alcohol. One could buy small amounts of alcohol in the camp canteen, until the Finns were denied this right due to continuous disorder. There were those who managed to brew spirits from potatoes, potato peels, soft drinks and yeast. They also bought alcohol from their German and Italian neighbours. The camp administration found out about this traffic, as the Italians and Germans tended to have more and more money, while the Finns were empty-pocketed. A specific kind of camp money was used; they started to mark it by nationality so that others could no longer buy anything with notes marked “F”. The note in the exhibition dates from before this division.

The quarrels had a sad outcome. A Finnish seafarer was stabbed dead by another Finn on 20.4.1943. The stabber was charged with murder; the legal consequence in Britain at that time was death sentence. The court, however, pronounced him not guilty, considering the deed self-defence. It is not easy to specify afterwards what exactly happened, as the authorities declared the court session secret. The case was taken up in a Finnish court of justice in 1956. The accused person pleaded self-defence here as well.

Conditions of the Finns in the camp

There are varying accounts about the conditions in the camp. Finnish seamen’s pastor Toivo Harjunpää was allowed to visit the camp on a monthly basis. He wrote in magazine Merimiehen Ystävä that the Finns were rather well off in the former hotel. They had cold and warm water, marine view and sufficient food. Risto Alanne, on the other hand, considered the food miserable, the dwellings cold and the rat problem bad. He further claimed that when he fell ill, he did not have the treatment he was entitled to by the Geneva Convention which the United Kingdom had ratified. Alanne said that the Manx treated the internees nastily; for instance young couples could intentionally come and make love near the camp fence.

The UK authorities argued that the camps were organized as required by the Geneva Convention. However, the Finns were not the only ones to complain of the conditions. A German internee, a medical doctor, assessed that the food contained insufficient vitamins, and he proposed improvements. Alanne says that the Finns managed to obtain vitamins with the help of the Swedish Embassy. This improved their health.

Whatever the conditions, years spent in a closed camp with practically the status of prisoner tried everyone’s endurance. Uncertainty about the future certainly made it worse. A Finnish seafarer was found dead in November 1943; the newspapers reported that he “fell from the window”. Emil Ahola remembered the case. It was his understanding that it was suicide.

At least part of the Finns had positive experiences on the Isle of Man. In magazine Kansa Taisteli in 1986, Emil Ahola described his work on a farm where several Finns worked. After the initial distrust, he made friends with the members of the household, and he kept contact with them after being released. Ahola also remembered the sports competitions with the German and Italian internees. He said that Finns were superior in track-and-field sports, but poor in football. The Finns were disappointed when the wards prohibited wrestling and boxing matches between the nationalities. The Finns had been training these sports in the gym they had furnished in the mattress storage.

The Finns on the Isle of Man could finally return home in late 1944. In September, 22 men who had fallen ill in the camp were sent home; the rest had to wait until December.